While the war raged on, in Italy the crowds of fans gathered in the stadiums where the Italian national team was playing, led by a technical commission. After the parenthesis of the Stockholm Olympic Games with Vittorio Pozzo, the only unpaid commissioner as per his wishes, the matches of the Italian national football team seemed to reflect the progress of European and government policy.

A draw and a defeat with Austria, the best of world football, yet another 2-0 win against France, followed by three games with neutral Switzerland, one draw and two wins for Italy. The first category football championship, divided into two groups, north and central-southern, was not only a sporting phenomenon, it was an integral part of the social fabric of the country, it fed passions, ignited controversy and great discussions.

The championship excites fans but the war is around the corner

On January 10, 1915 Inter wrote a memorable page in the history of football, beating Vicenza with the bombastic score of 16-0. The Neroazzurri thus matched the primacy of Genoa which two months earlier had trimmed the same number of goals to the Alexandrians of Acqui. These were the biggest wins ever achieved in the top Italian football championship, that had reached its 18th edition. The great political events of the imminent conflict between Italy and Austria marked the days preceding the last day of the final group.

Sunday, May 23th, 1915 the most important and decisive matches were scheduled. Meanwhile, parliament gave full power to the government for the war on Austria. However, the enthusiasm of the fans was still aimed at the national finals of the football championship. Genoa was one step away from winning the Scudetto. It was to meet Turin, and it only needed a draw to access the final against Lazio. And being again the strongest club in Italy. But Turin could also win.

Suddenly, all football tournaments stop

Following the mobilization of the army all match were suspended. With this short telegram, on Sunday, May 23, the Italian Football Federation notified the referees of the decision to stop the first category championship. This, due to the imminent war. Something happened, that no one had ever seen: the referees, turned into serious preachers, spoke with a single voice on different fields. They announced to the public, eager for distractions more than ever, and to the astonished players, that the party was over. They delivered a public reading of the press release with which the Italian Football Federation had established the immediate suspension of tournaments of all levels.

The referees, from North to South, return to the dressing rooms with the balls

At the beginning, people did not understand that afternoon games were also included in the measure. They started to realize what was happening only when the referees, from North to South, returned to the dressing rooms with the balls. Genoa and Lazio and the International Football Club protested in the major national newspapers. Vittorio Pozzo, technical director of Torino Football Club, a team in which he had played for five seasons before retiring from competitive activity, was not happy at all.

Just 15 days before the suspension, with a game of attack, the eleven grenade had beaten Genoa 6-1 at home. Correspondences from Corriere della Sera, La Stampa, Messaggero, Mattino, dell’Avanti, showed between the lines that Inter, beating Milan on the last day, would have reached Turin and Genoa at the top. In this way a triangular play-off would have been necessary before playing the final with Lazio, champion of the central-southern group.

The illusion that the war would soon be over

Following the protests, the leaders of the Italian Football Federation discussed the suspended tournament, convinced that the war would soon be over and victoriously, within a few weeks. And so they decided that the tournament would be completed when hostilities ceased. The declaration of war had not yet been delivered to the Austrian chanceries and for the Italians it was already a trauma.

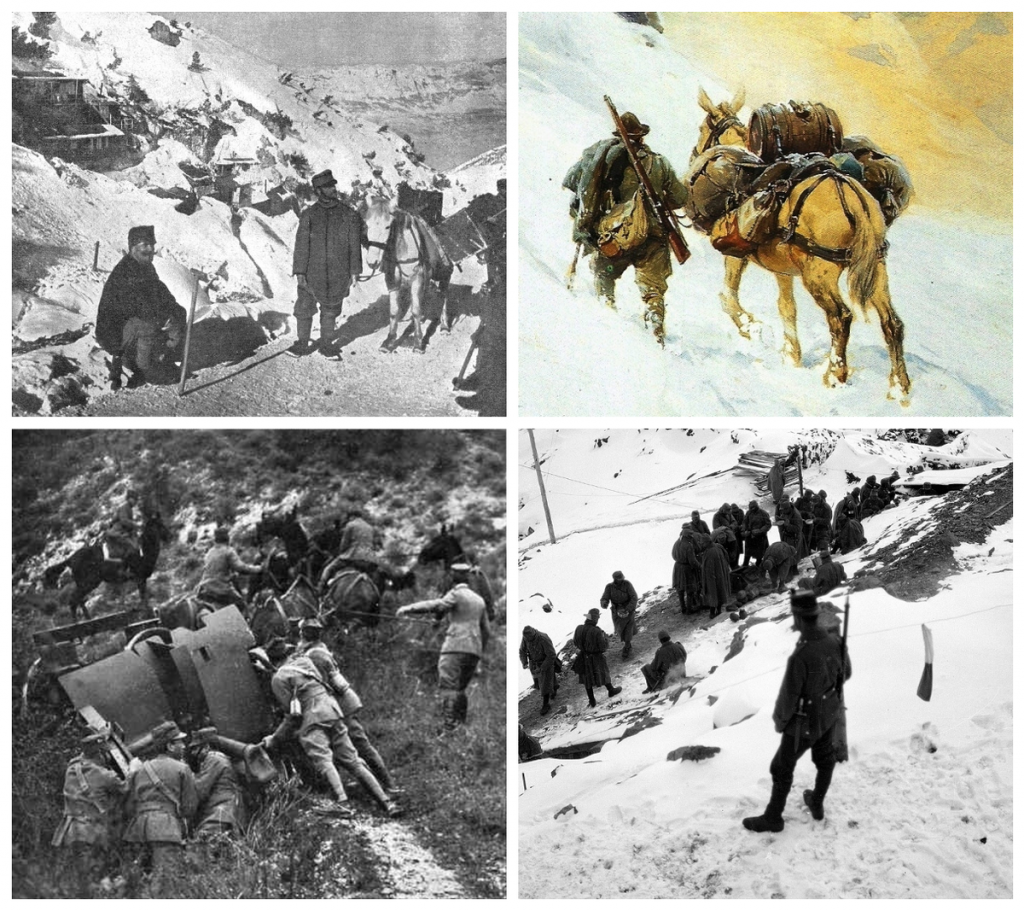

When sports stop, it means that events are exceptionally serious. This is the belief of all sportsmen. Players, as well as all the other Italian athletes, prepared to leave as soldiers, coloring the stadium bleachers with gray-green. A whole generation of young people was about to go to the front.

Enzo Ferrari, driver from Modena, worked as a mule driver and farrier; Tazio Nuvolari from Mantua with engines did not know what to do

Among the hundreds of thousands of soldiers there were also the champions of sport, unexpected protagonists of the war. Among these Fernando Altimani, the first Olympic blue medal for racewalk won a bronze medal in Stockholm 1912. Nedo Nadi, fencer, from Leghorn, Virgilio Fossati, driver of Inter and captain of the Italian national football team. And, again, the rower Giuseppe Sinigaglia, winner of the very important “Diamond’s Sculls Cup” on the Thames.

There was also the giant Erminio Spalla, the first Italian maximum weight to have international relevance that was divided between the passion for boxing and that for sculpture. Vittorio Pozzo was the lieutenant of the Alpine troops. His was an experience of moral rigor and education in the essentiality of the life of the trench that deeply marked him. With the stars on his jacket, the Modenese driver Enzo Ferrari was a muleteer and a farrier. Instead, Tazio Nuvolari from Mantua, an ambulance driver, was picked up by a senior officer because he didn’t know what to do with engines.

Even in the other armies engaged in the immense conflict, sportsmen shared the fate of their peers. The captains of the two Austrian and Italian national teams, Robert Mertz and Virgilio Fossati, who had exchanged the pennants, would no longer return to the pitch. Both fell victim during the conflict involving the two great nations.The match between Italy and Austria ended in a draw, 0 to 0, with no winners, like the war.